I know someone will ask me, ‘Do you really mean, at this time of day, to re-introduce our old friend the devil—hoofs and horns and all?’ Well, what the time of day has to do with it I do not know. And I am not particular about the hoofs and horns. But in other respects my answer is ‘Yes, I do. I do not claim to know anything about his personal appearance. If anybody really wants to know him better I would say to that person. ‘Don’t worry. If you really want to, you will. Whether you’ll like it when you do is another question.’

C.S. Lewis, Mere Christianity (1952; Harper Collins 2001) 45–46.

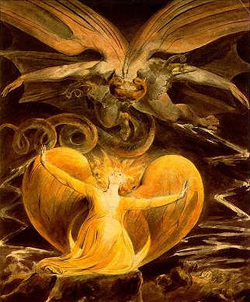

I did not choose texts about the devil for my St. John Passion to be sensationalist or controversial. I chose these texts because they represent the evil that permeates our world. In the last hundred years or so, if we are to speak about the redemption of humanity, I feel that archetypes of evil found in great literature are not only appropriate: they may be absolutely necessary.

When Elizabeth Davenport, dean of Rockefeller Memorial Chapel at the University of Chicago, asked me to write a new setting of the John gospel I immediately began pondering what texts I would use to add to the gospel narrative. As I was writing the music for the gospel text, I considered a wide variety of sources for other texts, from Whitman to revivalist church hymns. All paths of thought led me time and again to my grandparents and their various expressions of faith. Of course, there are differences between each of those individuals, but there is a central thread: the story of the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus Christ embodies a truth that permeates the world.

So, to me, this story had to be fictional and ineffective, or it had to be true and its effects perceivable in human history. There is not much of a spectrum between the two choices, even if there is a spectrum of (fallible) human reactions. Obviously, if I was going to write a large work based on the crucifixion story, I had to approach this story as a lawyer hired to defend one side and one side only. Bach’s passion settings and the story itself are engrained in me as both human and artist, so it is not a stretch for me, personally, to set this story to music. However, as I began to contemplate the twentieth century, Bach’s passions and even the story itself seemed less and less relevant. In Bach’s world, it is enough for the community to witness the portrayal of human beings sacrificing their god on Good Friday. Everyone is on the same page. It is terrifying because of there is no doubt about who Jesus Christ is: he is God.

In the twentieth century, and in recent political turns across the globe, the story of the execution of an ancient religious leader fails to conjure up the kind of unfathomable horror of World War II, to give just one example. Much of the present world continues to pat itself on the back for the political freedoms it claims to have bestowed on a wide variety of people, yet, when faced with catastrophes like climate change, one must wonder, “Just who is truly free and from what?” Are we really better than previous generations?

This led me to a working premise: if, in the crucifixion story, Jesus Christ died to redeem the world from evil, then that means all evil: past, present, and future; evil in which we consciously participate, and evil in which we are implicated unawares. Furthermore, God already knows this evil and, rather than take away the freedom of will granted to human beings, God lifts up a cross and carries it to Golgotha.

So, rather than choose texts that reflect upon the specific events of the passion narrative, I juxtaposed the passion story with classic texts that epitomize and contemplate human evil. Faust invites the devil in, unwittingly, and realizes too late that it is not so easy to get rid of him; Lady Macbeth asks that her entire being, mind, soul, and body, be possessed by evil in order to give free rein to her ambitions; and Dante paints a picture of departing hell via the very hair of Lucifer, who lies below the apex of the cross, surfacing to see perhaps the most breathtaking evidence of creation: the stars.

When Elizabeth Davenport, dean of Rockefeller Memorial Chapel at the University of Chicago, asked me to write a new setting of the John gospel I immediately began pondering what texts I would use to add to the gospel narrative. As I was writing the music for the gospel text, I considered a wide variety of sources for other texts, from Whitman to revivalist church hymns. All paths of thought led me time and again to my grandparents and their various expressions of faith. Of course, there are differences between each of those individuals, but there is a central thread: the story of the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus Christ embodies a truth that permeates the world.

So, to me, this story had to be fictional and ineffective, or it had to be true and its effects perceivable in human history. There is not much of a spectrum between the two choices, even if there is a spectrum of (fallible) human reactions. Obviously, if I was going to write a large work based on the crucifixion story, I had to approach this story as a lawyer hired to defend one side and one side only. Bach’s passion settings and the story itself are engrained in me as both human and artist, so it is not a stretch for me, personally, to set this story to music. However, as I began to contemplate the twentieth century, Bach’s passions and even the story itself seemed less and less relevant. In Bach’s world, it is enough for the community to witness the portrayal of human beings sacrificing their god on Good Friday. Everyone is on the same page. It is terrifying because of there is no doubt about who Jesus Christ is: he is God.

In the twentieth century, and in recent political turns across the globe, the story of the execution of an ancient religious leader fails to conjure up the kind of unfathomable horror of World War II, to give just one example. Much of the present world continues to pat itself on the back for the political freedoms it claims to have bestowed on a wide variety of people, yet, when faced with catastrophes like climate change, one must wonder, “Just who is truly free and from what?” Are we really better than previous generations?

This led me to a working premise: if, in the crucifixion story, Jesus Christ died to redeem the world from evil, then that means all evil: past, present, and future; evil in which we consciously participate, and evil in which we are implicated unawares. Furthermore, God already knows this evil and, rather than take away the freedom of will granted to human beings, God lifts up a cross and carries it to Golgotha.

So, rather than choose texts that reflect upon the specific events of the passion narrative, I juxtaposed the passion story with classic texts that epitomize and contemplate human evil. Faust invites the devil in, unwittingly, and realizes too late that it is not so easy to get rid of him; Lady Macbeth asks that her entire being, mind, soul, and body, be possessed by evil in order to give free rein to her ambitions; and Dante paints a picture of departing hell via the very hair of Lucifer, who lies below the apex of the cross, surfacing to see perhaps the most breathtaking evidence of creation: the stars.